ABETZ & DRESCHER

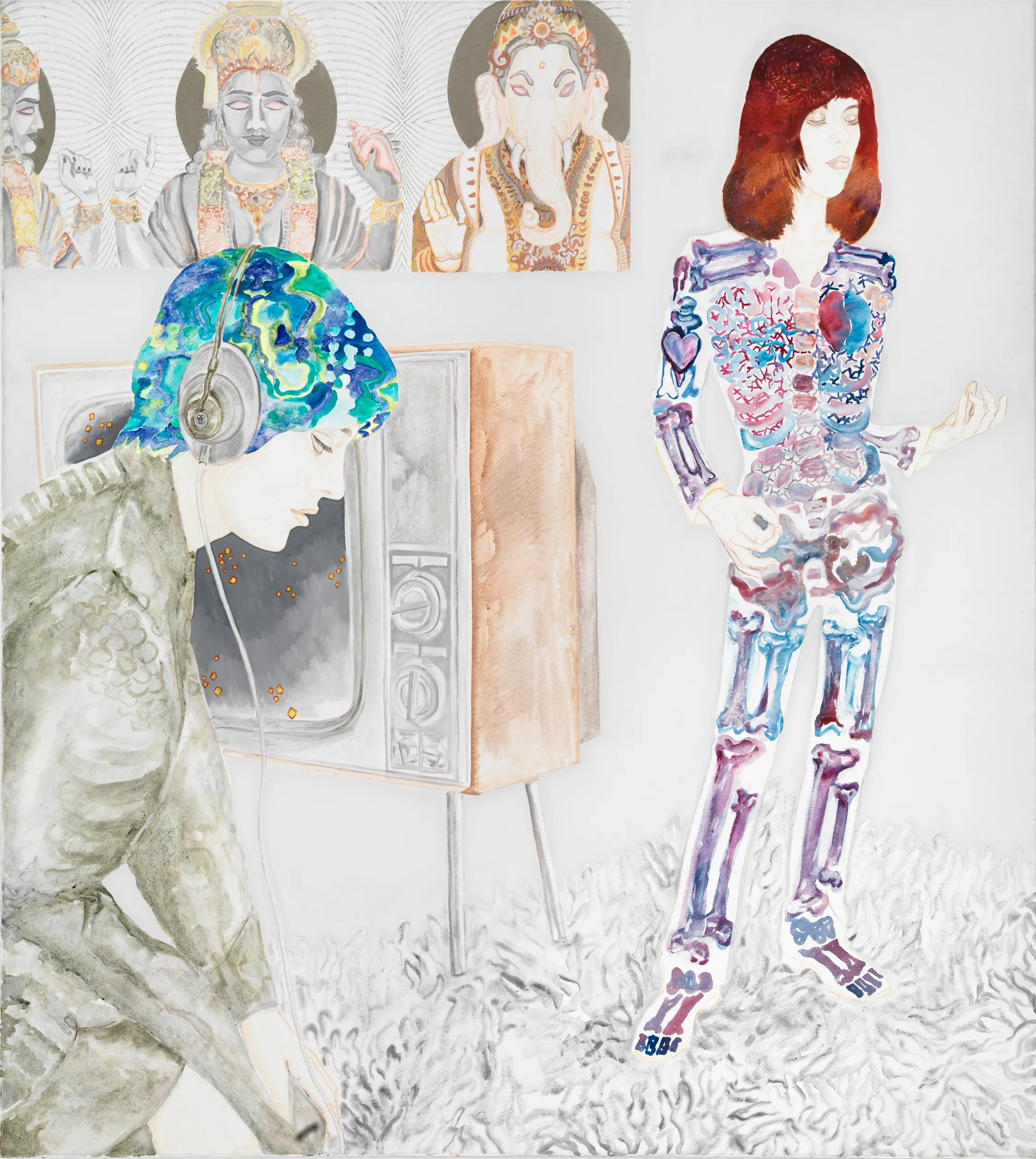

Their paintings embody dreams, illusions, hallucinations, and reflections of society using aspects of mass cultures such as music, art, and science fiction films as examples.

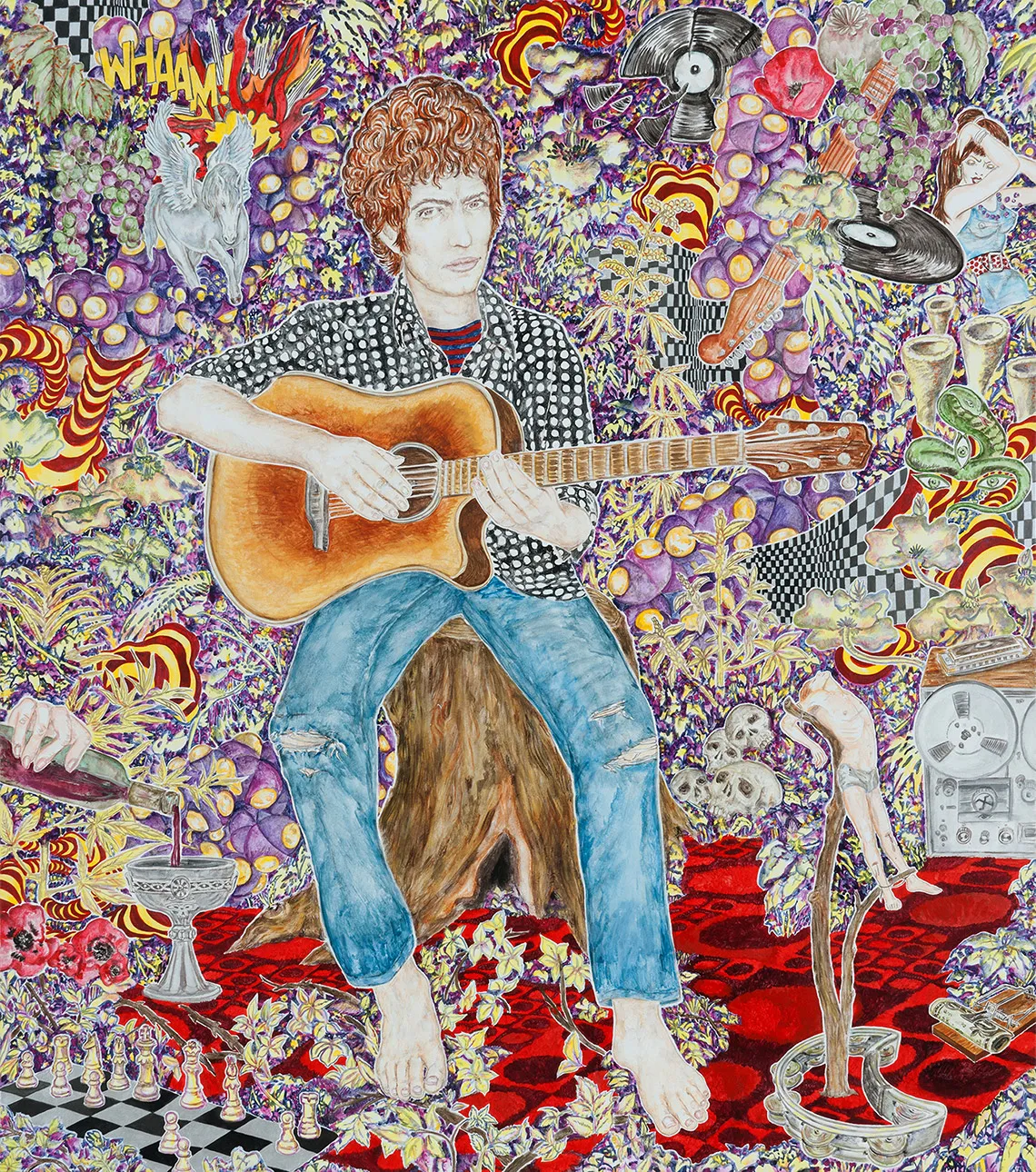

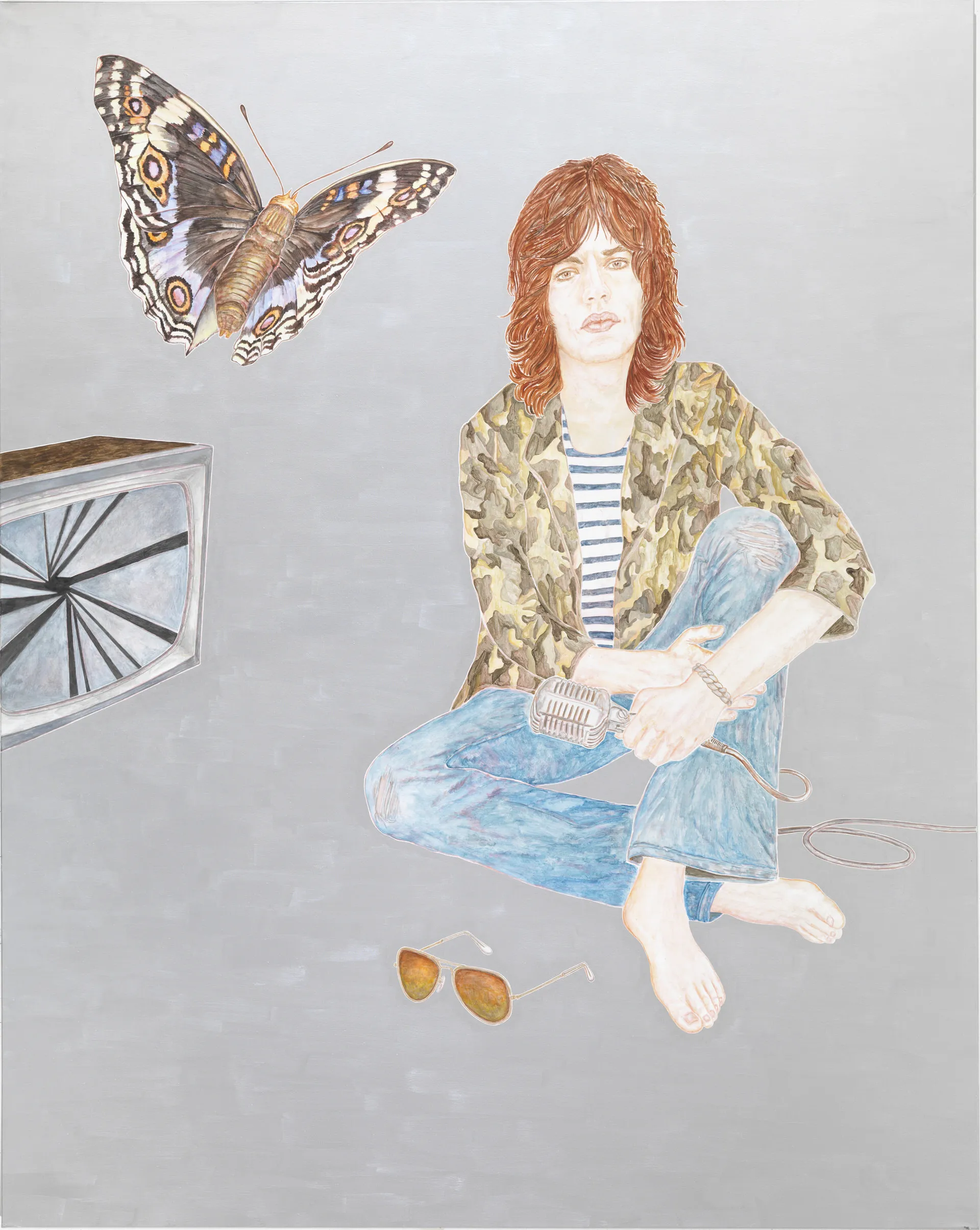

The couple creates a symbiosis that encompasses the period from the 1960s to the 1990s and includes icons of international music such as Mick Jagger, Jimi Hendrix, Bob Dylan, Eric Clapton, and The Who. These are immortalized in painterly representations, accompanied by their instruments and sometimes by the artists themselves, who are frequently staged as protagonists of their own narratives.

The result is the reproduction of a dynamic, diverse, lively scenario, immersed in a psychedelic world of mass culture as well as a journey into the past, including themes of the present and future. This suits the ideology and lifestyle of Abetz & Drescher, who regard music as a central figure in their works as well as a guide and reflection of society.

OEUVRE OF THE BON VIVANT

Maike Abetz and Oliver Drescher live their art, which is a faithful representation of their existence. There are countless artist couples who have seized their place in art history, such as Gilbert and George, Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Eva and Adele, Bernd and Hilla Becher, Elmgreen & Dragset, and Fischli/Weiss, and who – as the result of a symbiosis – conceive and realize their projects only as a couple. And, as Abetz & Drescher do, they also deal with painting, like Römer & Römer. Numerous exhibitions have focused on the theme of the artist couple or artist duo to distinguish whether both artists pursue their own artistic careers or, as with Abetz & Drescher, create collaborative artistic work . This artistic existence raises several questions: “ … creative exchange or influence? Rivalry? Self-empowerment of the female partner? Artistic and personal harmony?

Abetz & Drescher emphasize that when they met, there was a natural interest in common themes and a way of life, as well as the urge to invent something new for them- selves as enrichment for both. 14 From the very beginning, Maike Abetz was considerably interested in painting and focused intensively on pictorial characteristics and her role models. She euphorically tells us that the painter Sigmar Polke, who died in 2010, and especially his iconic work Höhere Wesen: rechte obere Ecke schwarz malen! (Higher beings commanded: paint the upper right corner black!),15 which was created exactly fifty years ago, had influenced her artistic practice. The banality of the title, the motif (black triangle on white ground), and even the banal rhyme (command – paint) could be references to spiritual influences, pure irony of the artist, or an effective way to defend an artist’s autonomy in the creative process by finding a distraction or excuse to distract the focus from his artistic decision. It was more than Polke’s attitude that attracted Abetz’ attention, also the way he composed his canvases and pictures in general: “Especially in Sigmar Polke’s paintings there are numerous traces of a changing society: trivial scenes, banalities of everyday life, petty bourgeois ambitions, national and international politics – these were the themes he dissected under the magnifying glass of his relent- less analysis. He delivered a unique version of reality, interspersed with irony, humor, and criticism. His alchemy combines intuition, planning, and chance, and the material also played its part. Experimental curiosity has always been one of his traits. It was also what drove him to play with all available techniques and genres: painting, drawing, gouache, photography, object art, films, and editions.”

Meanwhile, Oliver Drescher’s interests are mainly anchored in philosophy: “As philosophers, it is above all the French like Michel Foucault, Roland Barthes, Paul Virilio, Gilles Deleuze who should be mentioned. But the German media theorist Friedrich Kittler is also very important. I also studied with him. Sculptors would be those from the 1960s: Claes Oldenburg, James Rosenquist, Jasper Johns, Tom Wesselmann, George Segal. But also very important: Martin Kippenberger and Mike Kelley.” His primary focus is always considering the content, asking questions, and lending structure. At the beginning of his studies, he was interested in sculpture, which for him can transform thoughts into concrete forms.

But the symbiosis between Maike Abetz and Oliver Drescher finally crystallizes in painting. The use of acrylic paint on large canvases reflects the fusion of the two artists – their interest, their way of painting, aesthetic, and content-related arguments are summarized under the signature Abetz & Drescher, without leaving traces of the individual identities for the viewer. Their works correspond to the spirit of the Berlin art scene of the mid- 1990s and find significant resonance as a component of new German painting: “At first sight, the painting of Maike Abetz and Oliver Drescher, seems about to explode with colour, to be wallowing in the drastic vividness of a sixties revival, to primarily collect representatives of a pop culture getting a bit too long in the tooth, albeit shown in their prime as in the ‘Viva’ magazine. But the links go much further, ancient gods and baroque cherubs can also be found alongside arches from ancient Greece which suddenly flow into op-art ornaments. The pictures are time machines, they produce hyper-historical and, simultaneously, syn-aesthetical spaces which, in particular, transform the medium of music into the visual and unite codes to form densely staggered allegories..

Self Portraits

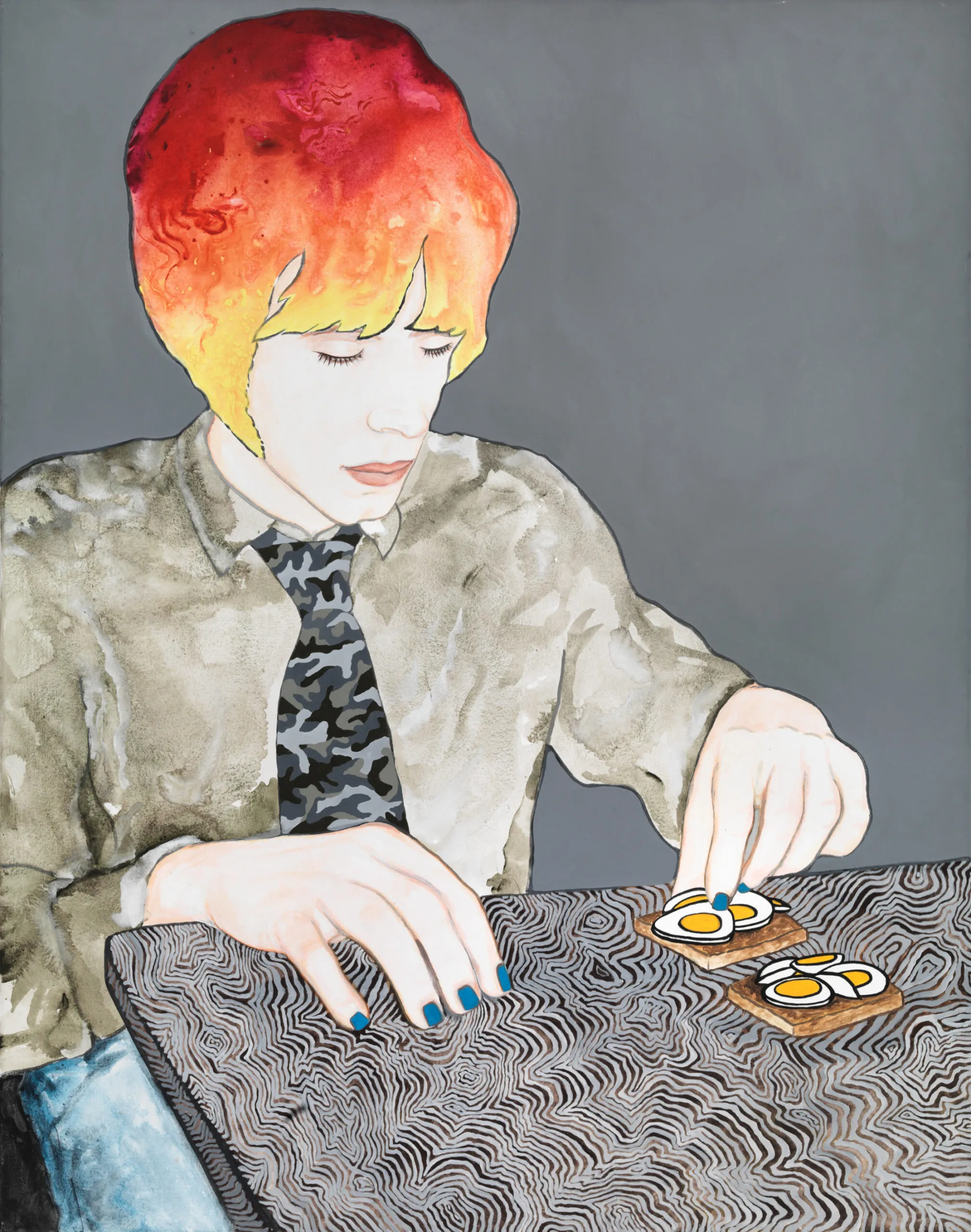

The genre of the self-portrait is a significant component of their oeuvre, either individually or integrated into their universe, which is shaped by music. In the style of the 1960s and 1970s, the protagonists are portrayed with the typical ornaments of the time. They are an integral part of their self-portrayal, staging, and perception.

Martin Kippenberger was a comrade-in-arms of self-dramatization, who repeatedly critically or ironically portrayed and questioned his own role. His first solo exhibition in 1981 at the nGbK (Neue Ge- sellschaft für bildende Kunst, Berlin) was titled Lieber Maler, male mir … (Dear Painter, paint for me …). It was an ironic reference to the role of the artist and his self-portrayal in painting: “Kippenberger’s title Lieber Maler, male mir … articulates a radical statement about the contemporary status of the painter.

His directive should be taken at face value: ‘Dear painter, paint me,’ ‘Dear painter, paint for me,’ or ‘Dear painter, paint me something,’ Kippenberger is not only making a sarcastic delegation of artistic responsibility but he is clearly confirming that the ‘dear’ figure of the painter has lost his cultural currency.” 19 This critical statement was partly due to the fact that the series of twelve works presented by Martin Kippenberger in the exhibition were the result of a commissioned cinema poster painter. His task was to imitate the artist in the poster motifs in his role as an artist.

The Artists Themselves

In addition to self-portrait, Abetz & Drescher’s figurative painting is always inhabited by two central figures: the artist themselves, who may pose for each other, as in the works Atmosphères (2000) or Up Against It (1997); female muses as divas and pin-up figures; or musicians who provide the inspiration for artistic creation through their songs. The homage is emphasized in the title of the pictures: Maria Callas, Jimi Hendrix, Mick Jagger, The Who, The Doors, Elvis Presley – numerous myths are celebrated with these persons and titles.

The color palette has an authentic relationship to legendary vintage pictures in a combination of orange, red, pink, blue, and silver. The main characters – especially in the “musician series” – are placed in front of a vivid background, the entire surface of which is part of the narrative. Individual scenes mix and the effect of the picture-in-picture hypnotizes the viewer. Attention is drawn to the magical, graphic representation of the myths. The eyes stroll restlessly in a dense, constructed landscape with animals, humans, plants, games, pleasures, and all sorts of excesses of life up to the representation of skulls. These intense, surrealistic compositions are reminiscent of reproductions of hallucinogenic experiments, for example, in the works Mick Jagger, The Doors, and Eric Clapton, all created in 2011.

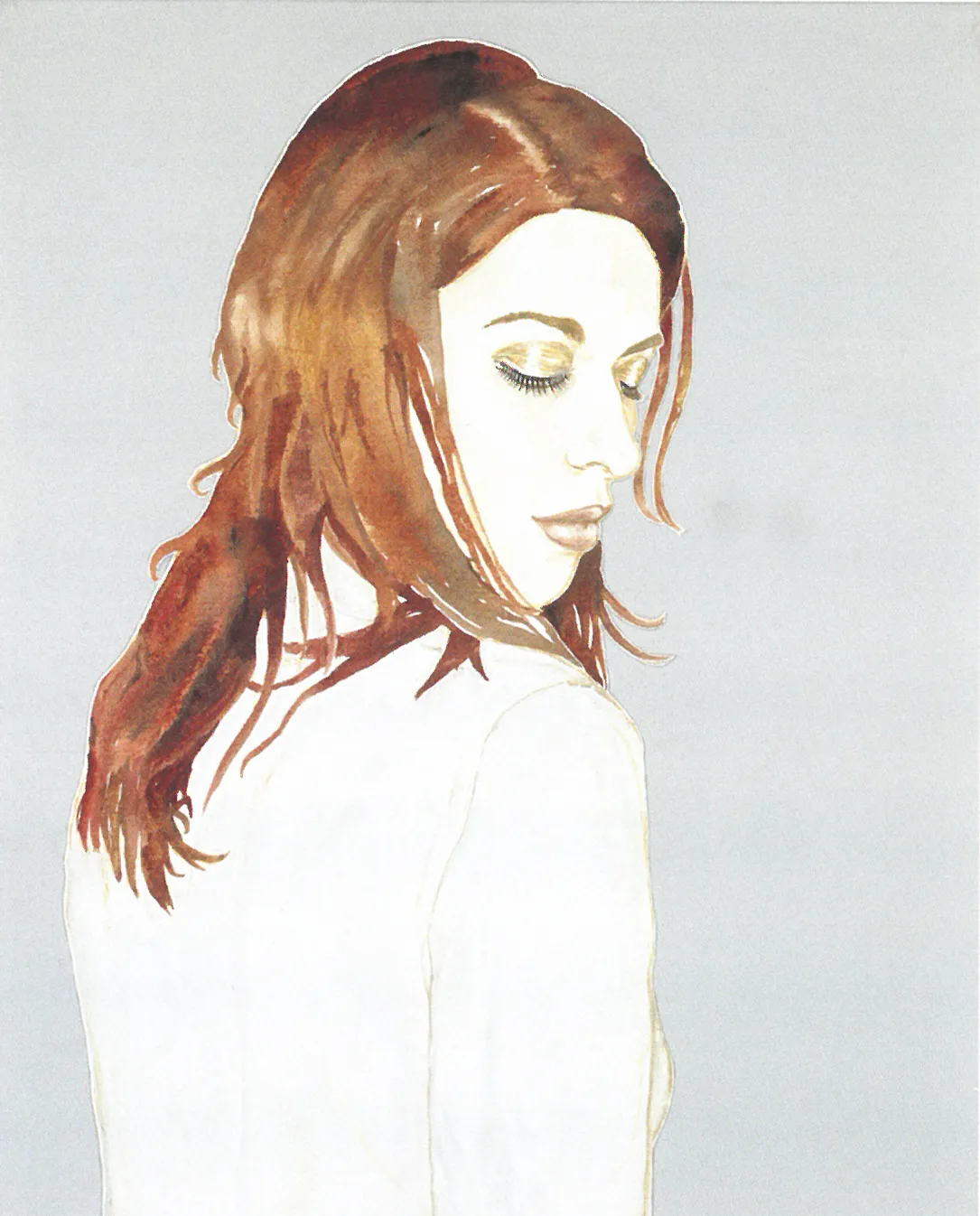

Female Figures

In current works created from 2017 onwards, female representations are celebrated by being presented as individuals centered in the picture. Their attitudes are sovereign, sublime. Their facial expressions and gestures invite the viewer into a direct dialogue. They are seated in interiors that look like room capsules. These are decorated with optical patterns that achieve the illusion of an in-depth perspective. Rooms such as those in the paintings Rebirth, Answer My Prayer, and Flashback grant a view of the out- side world through various openings. As if in a spaceship, the muse orbits the universe as though it were inviolable for humans.

Individual Elements

In the most recent works, the individual elements are now dissolved and extracted. Record players or guitars float in front of silver, monochromatic backgrounds like in Supernature, Soul Explosion, or Stardust (all 2019). Abetz & Drescher remain true to their icons and the traces they’ve left. They achieve an authentic oeuvre using the example of the bon vivant, who they adore and immortalize in their paintings.

Abetz & Drescher — On the Road, 2019, 200 × 250 cm, Acryl auf Leinwand

THE MYTH OF POP CULTURE

In the 1950s, San Francisco was already the beat generation’s stage. The protagonists were poets and writers who, together with visual artists such as Bruce Conner,19 defended a new aesthetic and programmatic approach with a critical view of social trends. Fifty years ago, the legendary Woodstock Festival took place. Thirty-two bands and solo artists performed in front of an estimated 400,000 visitors. The festival was a commercially uncoordinated event and embodied the longing for Love & Peace in a controversial political, social, and economic era.

In the 1960s, the counterculture was on the international agenda. The artistic move- ments, led by visual artists, writers, filmmakers, fashion designers, and musicians, defended the right to equality in society, regardless of socio-economic background.

It became a historical landmark of mass movements for protests that remain part of the contemporary socio-political agenda to this day: “The 1960s are often discussed in terms of revolution. Throughout the decade and around the world, a generation of young people took direct action, effecting a series of social and political transformations. Fifty years later, government policies resulting from such interventions render a way of life in the West that could have been unimaginable to all but the surest of sixties visionaries. The aesthetic legacies of the period persist, too, felt most strongly in the world of fashion, where so-called ‘bohemian chic’ continues to make its mark, conjuring memories of a turbulent yet hopeful period of American history. Intellectuals, philosophers, and poets of the day provided mounting evidence that change across all spectra of society was not only possible, but fundamentally preferable.”

The movement of the 1960s shaped and inspired Abetz & Drescher and is still decisive for their artistic development and work today. The realization of their exhibition Place Called Love at Kunsthalle Rostock reveals that certain themes, debates, and contexts are still present in the anniversary year of the “Summer of Love.” At the same time, it is a fortunate coincidence that Kunsthalle Rostock is also celebrating its fiftieth anniversary in 2019. The GDR’s only new museum building was opened in 1969. Through this exhi- bition, we are thus bringing two different contexts that exist simultaneously into a dialogue – on the one hand, the traces of pop culture that emerged in the West in the 1960s, and on the other, a cultural platform from the former “Eastern Bloc,” which to this day continues to play its role as a mediator of socio-cultural contexts.

Text by: Tereza de Arruda, Curator

Abetz & Drescher — A Place Called Love, 2019, 230 × 270 cm, Acryl auf Leinwand